Julian “The Philosopher,” Rome’s last Pagan emperor (mid-360s), would get chuckle out of this. (Although to me he comes across as super-serious, he must have found some things funny. I hope.)

While he was force-fed Christian theology by bishops, growing up in a royal Christian household, he later studied ancient Greek philosophy and literature extensively. Yet he was no bookworm: He was also a blood-and-guts Pagan.

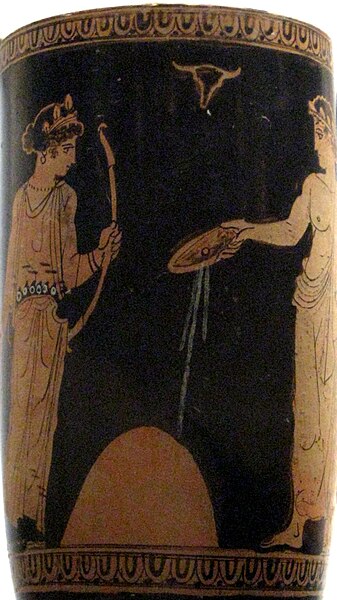

He did not just renounce Christianity by saying the Lord’s Prayer backwards, for her arranged a full tauroboium ceremony to wash away the Galilean stink. After becoming emperor, he brought back large public sacrifices as in the previous centuries:

I worship the gods openly, and the whole mass of the troops who are returning with me worship the gods. I sacrifice oxen in public. I have offered to the gods many hecatombs as thank-offerings. The gods command me to restore their worship in its utmost purity, and I obey them, yes, and with a good will. For they promise me great rewards for my labours, if only I am not remiss.

Some of his coins show a bull on the reverse, and numismatists are still asking why.

Another project that he backed financially was rebuilding the Jewish temple in Jerusalem, which Roman troops had destroyed in 70 CE when they smashed a Jewish rebellion in that province.

Polytheist that he was, Julian had no religious issue with the Jews (so long as they did not revolt against Rome), because their religion was very old. While Gentiles could and did convert, Judaism was not actively seeking them. Christianity was new and militantly opposed to all the old learning and the old gods.

Furthermore, rebuilding the temple in Jerusalem would frustrate Christian teachings that Jesus had predicted its destruction (Mark 13:2) and that the Christian church was itself the “new Temple.” Funds were allotted; then a small earthquake interrupted the work, followed by Julian’s own death in battle. End of story — or not.

For years, Texas businessman Byron Stinson has dreamed of a world at peace.

Some evangelical Christians like Stinson, as well as some Orthodox and Messianic Jews, believe the red heifer ritual described in the biblical Book of Numbers could pave the way to rebuilding a Jewish temple in Jerusalem. A new temple, which would replace a temple destroyed by the Romans in the first century, would usher in the kingdom of God, ruled by a messianic figure.

According to Numbers 19, the sacred ceremony — in which the cow is slaughtered and then burned — must take place on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem with a view of the site of the former temple, said Rabbi Yitzchak Mamo, president of Boneh Israel, an organization that works to build up and revive biblical sites in Israel and oversaw the practice ritual. . . .

Organizers admitted the idea of a red heifer ceremony could be troubling to some. But Stinson said that in the end, it could have powerful effects for the good.

Yes, it will be a little troublesome to thousands of Jewish rabbis, who took over religious leadership from the old Temple priesthood, and also to those Christians who think that what was done is done.

But there is that minority of Christians who believe that the Temple and the nation of Israel must be upheld in order to bring on their version of Jesus’ triumphal return.

Subscribe to this blog to read more on the academic study of Paganism and related Pagan topics.