About two days too late for this big bolete. The squirrels had already been at it, and most of it was too soft. M. said it was a Great Mother Mushroom and we had to leave her to spread her spores. OK.

Many of the Pagan bloggers are putting up their “Happy Lammas/Lughnasad” posts. My archaeoastronomical friends who study mysterious ancient solar alignments point out that “real” Lammas is still six days away.

But there is “the notch.” In 1986, when I moved to this part of Colorado, a friend told me, “Something changes around the first of August. It’s still hot, but there is a change.”

This year I really felt it. On July 30th I was standing out in front of our volunteer fire department at sunset — there was a little rain squall to the west and a partial rainbow to the east, and the air just felt . . . different.

Liatris is blooming too, the flower that marks the turn into High Summer.

After one quick trip on July 10th, M. and I geared up yesterday for our harvest. Never mind the garden, it’s mushroom time in the Southern Rockies. Off we went to the boreal (OK, subalpine) forest — up, up, up, about a 4,000-foot elevation gain.

A shock. Someone was parked in “our” spot on a certain dirt logging road. And a bulldozer had been working the road too — there is some salvage logging going on. We parked the Jeep a few yards further on. Shock again! Someone was camped up there—a vehicle and a blue tent.

On the warpath now, we communicated by signs and whispers. This way . . . circle right, check the little patch of woods we call “the mushroom store.” There’s a good bolete, grab it.

Then we come to the Forest Service drift fence, follow it to “the little gate” (there is also a “big gate”), walking quietly.

A man is calling a dog — “Sheena, come!” — on the other side of stand of firs. Into a further maze of old logging roads, now snowmobile trails in the winter, we plunge, walking quickly.

I stand in a clearing, waiting for the GPS receiver to access its satellites so that I can re-locate some good spots saved as waypoints a year ago. M. circles me, looking down. After years of mushroom-hunting in this area, I know the lay of the land, but how far up the edge of “the boggy meadow” was that good stand of Boletus edulis? Technology has its place.

Once we are a quarter mile from the Forest Service road, we start to relax. As so often happens, the farther from the road, the fewer people you meet.

In Westcliffe, the Wet Mountain Tribune, a weekly, headlines, “Shroomers are Coming.” The Search & Rescue volunteers will be ready.

The truth is, SAR spends most of its time on climbers falling off peaks in the South Colony Lakes/Crestone Needle area of the Sangre de Cristo Range. Go into their building, and the main room is papered with topo mags and photos of that area.

But there was Frida. She was one of the “old German ladies,” an acquaintance of Dad’s, and a member of the mycological group in Colorado Springs, as was he. Military town that it is, Colorado Springs has a population of German GI brides like her. Years ago, M. and I encountered some of them walking through the woods with their shopping bags on the back side of Pike’s Peak. They taught us some mushrooms (Dad was away in Washington state then.) They became iconic to us.

A decade or so ago, Frida was lost overnight in these mountains. She was found the next day, in good shape. But somehow Search & Rescue locked onto her as a type specimen of the absent-minded mushroom hunter.

For Christmas 2001, Dad bought us a memberhip in the mycological society. Colorado Springs was too far to go for membership meetings, but we hoped to rendezvous for their “forays,” as the serious mycophiles call them. We signed up for one — it was cancelled due to drought.

That was a dry year, big forest fires popping up, including the Hayman Fire that threatened suburban Denver. (“All of Colorado is burning today.”) And then Dad was gone.

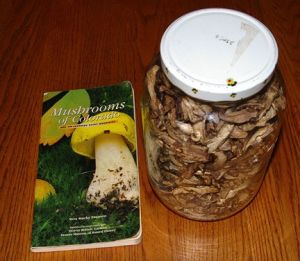

This is not a “foray,” this is a meat hunt. M.’s Opinel mushroom knife is flashing. Boletes. Hawk’s wing. Velvet foot. Even a puffball, just for bulk.

“We need to leave by 2:30,” she says. Other responsibilites. We make a wide circle back to the Jeep; then she steps behind a big fir with the bags while I, wearing just my day pack, stroll to it, start the engine, and drive down the road to pick her up.

We plan to go back on Thursday. That is almost solar Lammas — the Sun hits 15° Leo on Friday. It is really “Lammastide,” not “Lammas Day” — a short season. And we will be harvesting.

Like this:

Like Loading...

M. and I have been hitting the deep woods one day a week as part of the annual Mushroom Hunt. Yesterday was an odd one.

M. and I have been hitting the deep woods one day a week as part of the annual Mushroom Hunt. Yesterday was an odd one.